In Part I, I said there were 42 species of Birds-of-Paradise, but eagle-eyed readers would have spotted a little asterisk against that number. You see, I put a caveat there because that number has a nasty habit of fluctuating from year to year. For example, a couple of years ago it was 39, a couple of years before that it was 38, couple years before that it was 41. When John Gould’s1 posthumous study on the birds of New Guinea came out in 1888, he listed only 22 species. But by the 1930s that number had swelled to over 60. So, what the heck is going on?

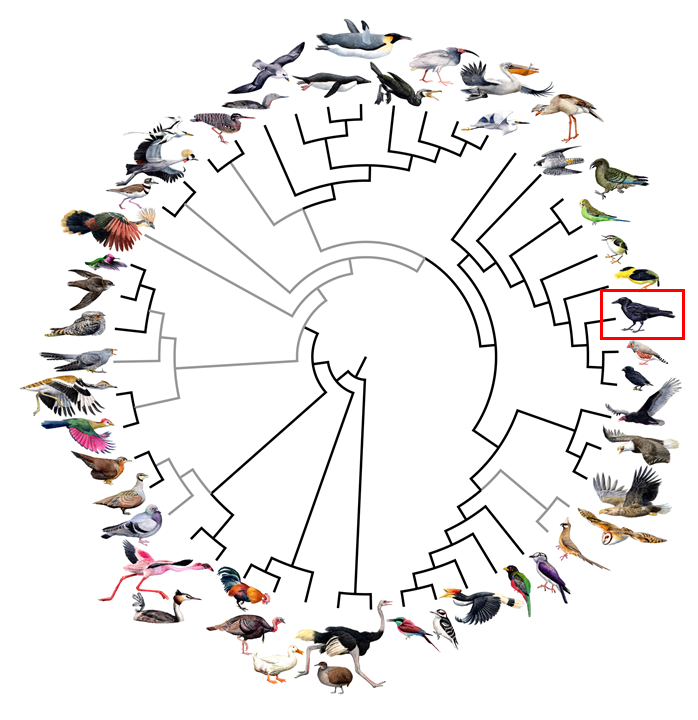

Before we get too deep (and I have gone deep on this one), we should take a moment to define what exactly a ‘Bird-of-Paradise’ is. That means it’s time to talk about tax. But I’m not talking about ‘axe the tax’ taxes. I’m talking about taxonomy: the system of classification used to categorise life.2 In the family tree of life, everything is broken down into categories, with individual species grouped with other animals they’re related to. If we begin at the top of the tree, we have all of life. Anything that’s alive is in this tree. Rocks are out, raccoons are in, clouds are out, clams are in, glass bottles are out, blue bottles are in. Viruses? Don’t ask about viruses, we haven’t worked that one out yet.

Anyway, you get the picture. Starting from all life we begin to split things up into Kingdoms. This is where plants and animals get split into their own groups. The animals get split again into all sorts of categories. For example, us Humans are in the Class Mammalia, whereas birds are in the Class Aves. From Class things keep getting split into smaller groups; the next one down is called an Order. For Humans, we are in the Order Primates. We are mammals, but we’re different to… say, dogs. Dogs are in the Order Carnivore, along with cats, otters, bears and whatnot; rats are in the Order Rodentia, with all rodents; and horses are in the Order Perissodactya, along with such things as zebra and rhinos. Anyway, we go one more step down and we hit the Family group. Our Family are the Great Apes (Hominidae). From there you go to Genus and finally Species. We Humans are alone in our Genus, but the Neanderthals used to be in there with us. Once you get to Species you can’t subdivide further. Our Species is Sapiens.

Now, back to the Birds-of-Paradise. What level are they at on this big old tree?

Let’s break it down. They are a bird, so we begin at Class Aves, with every other bird. Next, they are what is known as a perching bird, and they all belong to the Order Passeriformes. This is the largest Order of birds, nearly half of all bird species are in this single Order (that’s about 6,000 species). We go one more step down to Family, and here we hit Paradisaeidae.3 This is as far as we need to go, because we have now reached the group of birds that interest us. So, for comparison, the Family we belong to were the Great Apes. Which means here, we’re looking at birds that are as related to each other as we are to a Gorilla or an Orangutan. So now we know what an ornithologist means when they say that such-and-such-a-bird is a Bird-of-Paradise. I hope that made sense.

So, why has the membership of this Family been so volatile over the years? Well, getting to the bottom of that question is no easy task. But stick with me and I will guide you through the strange history of how ornithologists have attempted to grapple with this equally strange Family of birds.

To start us off, Gould’s number of 22 is so low for the simple reason that the jungles of New Guinea are some of the most isolated and famously impenetrable places on earth. To put it simply, Gould just wasn’t aware that those extra birds existed because they hadn’t been discovered. The last Bird-of-Paradise to be discovered was the Ribbon-tailed Astrapia during the 1930s.

The way we got from 20 odd species to some 60 has less to do with scientific discovery and more to do with high fashion. During the late 19th and early 20th Centuries the feather trade was in full swing. Every year, from all corners of the world, hundreds of thousands of birds were slaughtered for their feathers. They were packed up and shipped back to the milliners of Europe who turned them into hats for well-to-do ladies.

Many birds were exploited, but none more so than the Birds-of-Paradise. As we saw in Part I, they have some of the most stunning and unique plumage in the avian world. The story of how many new Birds-of-Paradise were discovered follows a similar script. First, an unusual skin would come across the table of a plume trader. Being familiar with the common skins they dealt in on a daily basis, the smart traders knew when they had something rare (and possibly expensive) on their hands. For the right price, they would sell their skin to a museum or eager collector.4 From there, a young ornithologist, hungry for fame, would snap up the bird, race to publish a description and win the privilege to name the never before seen bird. So, through a systematic process of mass butchery, we slowly found all the Birds-of-Paradise that we know today. Just exactly how many rare and unique birds went unnoticed and ended up as hats is unknown.

Now, you might be thinking that this is the answer to the mystery. We simply drove the rarer birds to extinction. I mean, hey, we’ve done it with so many other animals. And if it was to make a fancy hat, well, there are worse ways to go. But no, that is not the case. At least, we don’t think so. For the most part, the Birds-of-Paradise survived the fashion industry thanks to their unusual mating practices. As you will remember from Part I, only adult males sport the fabulous plumes so coveted by the fashionistas. By comparison, the females and juveniles are quite plain. As such, hunters only targeted mature males, while the females and the younger males flew under the radar. Thanks also to their polygamous mating practices, it meant a single male could mate with many females. So as long you had a couple of males left you could always rebuild the population. And so, after the collapse of the trade, their numbers more or less recovered.

Indeed, the Birds-of-Paradise have survived hunters for hundreds (if not thousands) of years. Local indigenous tribes had long hunted the birds for their plumes before any European set foot on the island. Granted, not on an industrial level. But the locals of New Guinea have long prized the plumes just as the ladies in Europe did. Although, not quite for the same reason. In a way it is ironic that in New Guinea it is the men who adorn themselves with plumes, while in Europe it was just the opposite. Not unlike the male birds, indigenous tribesmen created headdress and other garments out of the feathers to act as a sign of their virility.

Either way, we’re still sitting here with 20 mystery birds belonging to this family. Many of them were quite rare, with only one or two examples ever found. On top of which, no-one had ever seen them alive in the wild. So, if they didn’t go extinct what gives?

First, let’s take care of a couple of the easier ones to explain. Let me introduce you to two Birds-of-Paradise you’ve probably never heard of: MacGregor’s Bird-of-Paradise5 and the Sickle-crested Bird-of-Paradise. MacGregor’s Bird is rather plain when compared to the other members of the family. It’s almost totally black, save for a streak of yellow under its wings. Its only real piece of ornamentation is a pair of yellow wattles around its eyes.

The Sickle-crested Bird is a little closer to what we would expect. Males have a stunning orange back and wings, as well as an ornamental crest. For many years, these birds and some of their close realtives6 were all included in the family Paradisaeidae.

Slowly though, ornithologists grew suspicious of MacGregor’s Bird. It just didn’t behave like a Bird-of-Paradise is suppose to. For starters, males and females look the same and they form pair bonds. Now, that wasn’t a deal breaker straight away, after all the Paradise-crow and Manucodes do as well. But then, when they looked at the Honeyeater Family they started to notice that MacGregor’s Bird had more in common with them. And sure enough, when we developed the technology to genetically test them, it turned out they were indeed just Honeyeaters masquerading as Birds-of-Paradise.

At first glance, the Sickle-crested Bird looks like a more promising contender. Their behaviour is more consistent with the Family: females lack the fancy plumes, and they have polygamous breeding habits, with the female taking on all of the chick rearing responsibility.

But the story ended up being the same. With more thorough genetic testing it turned out they weren’t related at all. In fact, they aren’t closely related to any other bird, so they got their own Family (Cnemophilidae) and are now known as Satinbirds. In the early 2000s,7 MacGregor’s Bird and the three new Satinbirds were shifted out of the Family and into their proper homes. This probably shouldn’t come as a surprise, though. As we saw in Part I, the thing that makes the Birds-of-Paradise so amazing is the wide diversity within the Family. I mean, at one end you’ve got a crow-like bird, at the other something with so many colours it’s called a disco-ball and in the middle there’s a thing with head-wires. So, because there aren’t many visual cues to unify the Family, it makes it easy to mis-classify a bird.

It has only been with more advanced techniques that we’ve gotten to the bottom of this question in recent years. Either way, that explains where some of the birds went, but after all that we’ve only account for four species. What about all the others?

When I was young lad, I used to love collecting a series of bird cards that came free in packs of Kinkara Tea. Sadly, the company no longer exists. But one of my favourite birds in the series was number 16:8 the Exquisite Little King Bird-of-Paradise. What a name! Its description read:

The Exquisite Little King Bird-of-Paradise is similar in size to the other ‘King’ varieties, and has curved, intermediate, wire-like tail feathers with incurved webbed tips. It is found in the locality of Salwattle at the North-western corner of New Guinea, and frequents the lower trees of the less dense forest, living on stone bearing fruits. It is active, constantly hopping or flying from branch to branch and fluttering its wings, and elevating and expanding the beautiful fans with which the breast is adorned.

That’s quite a detailed little description of its appearance and behaviour. I quote it in full, because it’s rather remarkable they have that information, considering no-one has ever documented this bird in the wild. Nevertheless, you can’t deny, it is a rather brilliant looking bird.

Why the good people at Kinkara opted to give this bird its more uncommon but extravagant name, I don’t know. Properly, this bird is know as the King of Holland’s Bird-of-Paradise9. It was first described in 1875, and even features in Gould’s study of New Guinea’s birds. But from 1875 until today only 26 individuals were ever collected, all during the height of the feather trade.

The first skins to come out of New Guinea made their way to the naturalist, A. B. Meyer10 in Germany, who provided its first description. Not long after this a request was made to show the skins to their namesake, King William III of the Netherlands. The King took a liking to them, and what with one thing and another and the whims of royalty, the skins never got returned. In fact, they still reside in Amsterdam to this day. Over the years a couple more specimens turns up. The famed collector of dead animals, Walter Rothschild4, managed to get his hands on no fewer than ten of these rarities. But still, no-one had ever studied a living one in the wild. Then the feather trade came to an end. No more were found, and for several decades they slipped into legend. Today, though, we’ve worked out the mystery.

King of Holland’s Bird-of-Paradise isn’t a species unto itself, it’s a hybrid. It’s what you get when a Magnificent Bird-of-Paradise mates with a King Bird-of-Paradise. A close examination of both parents reveals that their offspring have many shared characteristic. It has the breast epaulets that are unique to the King Bird, while its golden back is typical of the Magnificent Bird.

For my money, though, the real give away is its tail: an almost perfect blend of the two. The King Bird has two long wire-like tail feathers that end in tightly coiled disks of green feathers. Meanwhile, the Magnificent Bird has two long curly wires without feather filaments at the end. In the King of Holland, we see something halfway between the two, with a curly tail that has green filaments at the end, but instead of coiling into a disk they’re loose and opened. To really seal the deal, the King Bird and Magnificent Bird are also closely related. They both belong to the same genus, Cincinurrus, and share ranges in New Guinea that frequently overlap. It would not be outlandish to suppose that the two would meet each other in the forest from time to time, and if one female should have a wondering eye … well, what happens in the cloud forests stays in the cloud forests.

So that explains why this bird was crossed off the official list, but it is for the same reason that the other 20 rare birds were as well. That’s right, all the mysterious birds that were discovered during the feather trade were deemed to be hybrids that had arose through different combinations between the various species. At this point, we must introduce an important player in our story, Erwin Stresemann (1889-1972).

Stresemann was one of the most influential ornithologists of his generation, straddling the period between the age of the gentleman naturalist and modern scientist. He literally wrote the book on birds, Aves, a comprehensive account of bird behaviour, morphology and evolution. It would not be matched in scope or depth for decades. At least two birds that I know of were named after him (Stresemann’s Bristlefront and Stresemann’s Bushcrow). He’s kinda a big deal. So, when Stresemann spoke people tended to listen; and in the 1920s something was troubling him. He found it strange that of the 60 or so recognised Birds-of-Paradise, about 40 well rather common and well documented, while about 20 were only known from one or two trade skins. Why were they so rare?

Through a chance exchange with our old friend, Walter Rothschild (keeper of the dead), a specimen of one of these rare birds made its way to the Berlin Museum where Stresemann worked. It was a beautiful species known as Mantou’s11 Rifle Bird.

Like other Rifle Birds it had a blue patch of iridescent feathers on its throat. It had a dark violet head, with a jet black underside, along with filamentous flank plumes. Looking closely at this bird, Stresemann became convinced that it was the product of hybridization between the Magnificent Rifle Bird and the Twelve-wired Bird-of-Paradise. Once again, the two birds are closely related, and even in the wild, there have been documented cases of female’s visiting the display sites of the wrong male (not that Stresemann knew this at the time). Stresemann was convinced: Mantou’s Rifle Bird was a hybrid, the product of mismatched parents.

But then Stresemann got to thinking. If this was the case for one bird, then maybe the same would hold true for all of the other strange, illusive birds. So he set about tracking down these oddball birds, examining their plumage and comparing them to the other well-known species. In the end, he became convinced that the origin behind each of the 20 or so problematic birds could be explained in this way. He published his theory and the ornithology world kinda went … yeah, sounds good. Those strange birds were all reclassified as hybrids, banished from the official lists, never to be spoken of again. To Stresemann’s credit, his theory has stood the test of time: no bird he deemed to be a hybrid has ever been found since the end of the feather trade, and no bird has been given its official status back.

Given the mating practices of the Birds-of-Paradise, there is much to be said for the theory. In Part I we discussed how male birds are often overly keen to mate with anything resembling a female that crosses their path. Immature males that are yet to develop their fancy plumes can even inflame the passions of their elders. Young male Birds-of-Paradise often look exactly like females. These younglings will frequent adult display sites to watch the mating rituals and learn from the masters. If they get too close though, sometimes it can prompt an overly eager male to project their courtship display in the wrong direction. That being the case, it is not hard to image that should a female of the wrong species happen to stop by a male’s count, there is every chance he would mate with her, if she was willing. As we also saw in Part I, although there are striking differences between the males of each species, this isn’t the case with the females. In fact, they all look remarkably similar. A sex crazed male that can’t tell the difference between a male and female, probably isn’t going to notice if his prospective partner is of a different species.

Of course, while this explanation is completely plausible, it’s also difficult to know exactly how often it happens, and when it does, how often such mating leads to viable offspring. Nevertheless, it must happen, because there are plenty of examples cropping up between numerous species.

Indeed, among these mysterious birds, many are unquestionably the result of mis-matched partners. There are some truly beautiful birds that carry intermittent feathers from both parents. Or at least, we assume in life they would have been beautiful. Sadly, today we only have the sometimes tatty preserved remains and artist’s impression to go off.

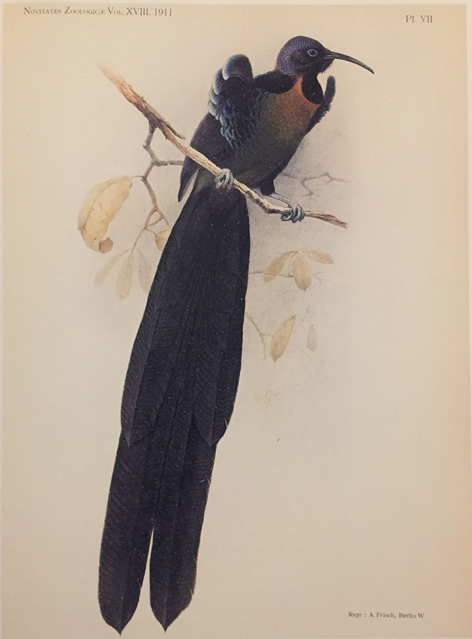

The Astrapian Sicklebill in one such stunning bird. It is believed to be the offspring of a Black Sicklebill and an Arfak Astrapia. Keep those two parent birds in mind and we’ll come back to them later. For now though, you can see in this painting the strange features which mark it as a hybrid.

It has the bill and epaulettes of the Sicklebill, while its broad magnificent tail is that of the Astrapia. Although the parents aren’t of the same genus, the two are still closely related. To add further evidence to the theory, both birds share overlapping territory on the Vogelkop Peninsula where it is believed this specimen originated from.

Another gorgeous example of hybrid displaying intermittent features is Wilhelmina’s12 Bird-of-Paradise. Only three specimens were ever collected, and it is suspected that they arose from a crossing of the Superb Bird with the Magnificent Bird. Its breast shield has the metallic blue colouring of the Superb, yet with the shape and structure of the Magnificent’s which is more of a pad.

Likewise, its tail is also a tell-tale sign of its mixed heritage. The Magnificent has two curly and crossed wires, while the Superb has a rather normal tail. While Wilhelmina’s Bird does not have the strong wires of the Magnificent, it does have two prominent plumes that extend from its back. Almost as if it were a toned down version of the Magnifient’s tail.

By now you might be asking, ‘well, if these birds can occur, why didn’t they just breed themselves and produce a stable race of halfway birds that became their own species?’ Great question. To answer it we will have to talk genetics. You see, hybrids are rare, but the only thing rarer than a hybrid is one capable of having children itself. You may be familiar with a mule, the hybrid of a horse and a donkey. But there is no mule that can have children of its own. Nearly all hybrid animals are born infertile. The reason for this has to do with the way sex cells are made. When an individual with parents of the same species comes to make its sex cells it will shuffle the genes it has that came from its mother and father. So a gene that codes for eye colour that came from the father will get swapped with the one that came from the mother; ditto with genes that code for things like tail length, feather structure, feet size etc. It’s one way genetic diversity is created in the next generation as different traits get mixed and matched. As long as both parents are of the same species all the genes for each feature will be found in the same place, so when the swapping happens, like for like genes get swapped out. If however, you’re a hybrid … well, now the genes may not all occur in the same place, so a tail gene might get swapped for a beak gene. If this happens you get sex cells that just don’t make sense, leaving the animal infertile. So no children for you.

Now we can start to understand why these hybrids are so rare. First, it’s probably a rare occurrence for unrelated species to mate at all. Second, there is only a low chance that even when they do mate that a live child would result. Then, even if you beat those odds, there is no chance that any resulting chicks could breed themselves. The game is really rigged against hybrids coming about. In some ways that’s a shame, because the examples we have of hybridization with Birds-of-Paradise are all amazing. One of my favourites is Captain Blood’s Bird-of-Paradise. I mean, is there any other bird in existence with such a badass name? This hybrid is so rare that only one specimen was ever found.

It is widely believed that Captain Blood’s Bird-of-Paradise results from the pairing of the Blue and Raggiana’s Bird-of-Paradise. But again, so rare must this coupling be, with such a small chance of producing live offspring, that there has only ever been one recorded case. In 1904 Captain Neptune Blood (again, what a name!) had established a lucrative trade, where he captured many Birds-of-Paradise for zoos and aviaries all over the world. But then, he stumbled on this odd bird, the size and shape of a Blue Bird-of-Paradise, but with the russet colouring of the Raggiana. Given the utterly bizarre mating ritual of the Blue Bird, where it hangs upside from a branch, pulsating its tail while emitting the oddest electrical hums and squawks, makes one wonder how some other species would ever become confused enough to mate with. Especially when the females are so particular about who they pick for their mates. And yet, there must have been at least one female with an kink for the unusual, because here’s the proof.

In the end though, it was the rarity of these birds, coupled with the fact that so often they possessed characteristics intermittent between two well-known species, that was to be the final nail in their coffin and the evidence the ornithological world needed to accept Stresemann’s theory. With the publication of his paper, these birds were all struck off the list and that seemed to close the chapter on these odd birds. Since that time, they have been all but forgotten.

Except … our story isn’t quite finished yet. Stresemann was maybe a little single-minded in his quest to include every mysterious and rare bird in his theory. Now, I must level with you: I have done a little cherry picking here. So far I have only spoken about birds where there is broad consensus that they are 100% hybrids. But there are many cases where the evidence is a little lacking. For example, the Mysterious Bird of Bobario (yes that’s its real name) had characteristics similar to those of a Sicklebill. However, only one specimen was ever found and its tail is missing, making it almost impossible to form any real idea as to what it looked like alive, and who its other parent may have been. Without another specimen we’ll just never know what it’s true nature is.

But then there are other birds, where it seems that Stresemann may have been way off the mark. There are two in particular. Elliott’s13 Bird-of-Paradise is the first. This bird even featured in John Gould’s study on the birds of New Guinea. After Stresemann was done though, it was relegated to hybrid status.

Stresemann believed it resulted from the coupling of the Black Sicklebill and an Arfak Astrapia. Ah, but you may recall that this is the same pair he suggested were behind the Astrapian Sicklebill. Stresemann didn’t seem to mind this contradiction. But even if we ignored the fact that there is a double-up happening, there are other problems. The collected specimens of Elliot’s Bird are all smaller than either of the proposed parents. It also has a lobe around its bill and an oddly shaped tail that neither of the parents have. To account for this, Stresemann suggested a Paradigalla may have also been involved…

It is unclear if Stresemann was hinting that this bird was the hybrid of a hybrid, he kept things vague. At any rate, rather than say this bird didn’t quite fit his theory, Stresemann seemed determine to account for every rare species, so he pressed on and declared this one a hybrid. And a hybrid it may well be, but given the apparent inconsistencies it is maybe premature to call things settled. Only a proper DNA analysis will tell us for sure, but to date this has not happened. For now, the best we can say is, we just don’t know what this bird’s deal is.

The second oddity is Rothschild’s Lobe-billed Bird-of-Paradise (named after our old friend Walter). Only two specimens were ever found. Unlike Elliot’s Bird that at least resembled a Sicklebill, Rothschild’s Bird is unique in the sense that it doesn’t really look like anything else.

Stresemann suggested the Paradigalla and the Superb Bird for its parents, and while it explains some features it misses others. For example, if this was the case, why does its feathers have purple and green hues, two colours that neither of the parents possess. And what of the strange lobbing around the bill? Trying to find a better parental combo doesn’t help much in this case, because then how would you explain the lengthened feathers around the neck, which only the Superb Bird has? The fact that it also bears a resemblance to another rare species, Sharpe’s Lobe-billed Rifle Bird14 (so close in fact that for a time the two were considered to be members of their own genus) only further complicates things. It’s just a straight up strange bird, and we really know nothing about it.

So what does this all mean? Well … it’s hard to say. In total, only two examples of either bird were ever found. They were never seen alive in the wild, and the specimens that we do have aren’t in the best condition. Given their rarity and the tendency Birds-of-Paradise have to sometimes mate outside of their species, it is possible that they are hybrids. Equally possible, though, given the odd features that are difficult to explain, there is just as much chance that they were rare birds already on the point of extinction when they were found and are now lost to the world forever.

There is a third possibility, though. Somewhere in New Guinea’s impenetrable forest covered mountains, these birds still live. Maybe it’s a long shot; but before I close let me introduce you to one last bird: the Bronze Parotia.

Like many of the mysterious birds I have mentioned, the discovery of the Bronze Parotia follows the same story. It was discovered during the height of the feather trade in 1897 and was given the name Berlepsch’s15 Six-wired Bird-of-Paradise, placed in a dusty draw and then forgotten. At the time, only five specimens were ever collected, with three ending up in the collection of Walter Rothschild. Stresemann never claimed this one to be a hybrid, but just like our other birds, it was never witnessed in the wild and another specimen never turned up after the collapse of the feather trade. Then, in 2005, a team of scientists exploring the Foja Mountains rediscovered it alive and well16. On that same expedition they also discovered a hitherto unknown species of Honeyeater, the Wattled Smokey Honeyeater17.

These recent discoveries give cause to hope. Who knowns what else might be hiding out there. It has happened once, so maybe it’ll happen again. I do hope that somewhere in a remote corner of New Guinea there is an oddly beautiful bird that has evaded humanity for over a hundred years. One day we may find it. Until then, they will remain a tantalising mystery of the avian world.

24/10/2020

There are few detailed writings on the hybrid Birds-of-Paradise that are readily available. While preparing this essay I relied on Errol Fuller’s The Lost Birds of Paradise (1995).

Notes

[1] John Gould (1804-1881) was one of the most famed and celebrated ornithologists of his generation. He produced numerous lavishly illustrated studies on birds, from Australia, New Guinea, England as well as South American Toucans and Hummingbirds.

[2] A good explanation of taxonomy and how life is classified is beyond the scope of this piece, but for those who are interested I recommend this explanation.

[3] It’s actually a little more complicated than that. Because the Order Passeriformes is so large there are intermediate groups between Order and Family. So, for completeness sake, Birds-of-Paradise actually belong to the Sub-Order Passeri, which are the songbirds. From there they belong to the Superfamily Corvoidea, which is the group Crows and Ravens belong to. As was mentioned in Part I, the closest relatives of the Birds-of-Paradise are the Ravens.

[4] The most famous private collector was Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild (1868-1937). He managed to amass the single largest private zoological collection of the time. At its height he had over 300,000 birds, 200,000 birds’ eggs, not to mention well over 2 million butterflies. Many of the rarest Bird-of-Paradise specimens were held in his collection. He even had one named after him: Rothschild’s Lobe-billed Bird-of-Paradise.

[5] Named for Sir William MacGregor (1846-1919), the Administrator and later Lieutenant-Governor of British New Guinea. His wife, Mary Jane Cox also has a bird named after her, MacGregor’s Bowerbird.

[6] Along with the Sickle-crested Bird-of-Paradise, its closest relatives were the Yellow-breasted Bird-of-Paradise and Loria’s Bird-of-Paradise.*

* Named for the Italian anthropologists, Lamberto Loria (1855-1913), who spent seven years exploring New Guinea.

[7] This finding resulted from a study conducted by Joel Cracraft and Julie Feinstien, ‘What is not a bird of paradise? Molecular and morphological evidence places Macgregoria in the Meliphagidae and the Cnemophilinae near the base of the corvoid tree‘ (I know, what an amazingly catchy title for a paper).

[8] There were 480 cards in the whole set. Yes, I have the whole set.

[9] Like so many other Birds-of-Paradise, this one is named for a royal patron, King William III of the Netherlands (1817-1890).

[10] Adolf Bernhard Meyer (1840-1911) was a German naturalist, famous for translating the works of Darwin and bringing ideas of evolution to German science. He travelled to South East Asia himself and collected many new specimens. He was the first to describe two other Birds-of-Paradise: Queen Carola’s Parotia and Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia. He is also commemorated in the Brown Sicklebill, whose scientific name is Epimachus meyeri.

[11] We know little of who the Mantou of Mantou’s Rifle Bird was. Only that he was a Parisian plumassier (one who trades in ornamental plumes). He identified the bird as being something different and donated it the Paris Museum. For his troubles he got it named after him.

[12] Another bird named by A. B. Meyer. He must have had a thing for the Dutch because Wilhelmina of the Netherlands (1880-1962) was the daughter of William III. She came to the throne at the age of ten after her father’s death.

[13] Elliot’s Bird was named for the American ornithologist, Daniel Giraud Elliot (1835-1915). In 1873, when the bird was discovered, Elliot was about to release his own study on the family. One of the artists John Gould often worked with, Joseph Wolf, had been able to study and draw the bird, and its first depiction even appeared in Elliot’s study.

[14] Named for the naturalist and artist, Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847-1909). It was Sharpe who finished and published Gould’s final study on the Birds of New Guinea after he died. Sharpe was also to publish his own study on the Birds-of-Paradise, which in my opinion is the most beautiful of any produced. Here is a video of David Attenborough talking through a reprinting they made of it several years ago.

Sharpe’s Lobe-billed Rifle Bird is itself a mysterious specimen of which only one example was ever found. It’s believed to be a immature bird as well, which only complicates things more as its full plumage probably hadn’t developed. Numerous parents have been suggested to account for its strange features, with the Paradigalla and a Parotia generally accepted as being the best guess possible with such limited information.

[15] Named for German ornithologist, Hans von Berlepsch (1850-1915).

[16] The popular science writer, Jared Diamond, began his career as an ornithologist and spent time in New Guinea. During the 1970s he spotted several female Parotias in the Foja Mountains and speculated that they may have been the lost bird, but without seeing one of the distinctive males it was impossible to say for sure. This tantalizing hint spurred the expedition of 2005, which was led by Bird-of-Paradise expert, Bruce Beehler.

[17] It became the first new bird discovered on New Guinea since 1939 when the Ribbon Tailed Astrapia was found.

Thanks for the informative and entertaining essay Nathan. Kinkara tea is still available – I drink it every day – though they stopped the bird cards many years ago.

LikeLike

Ohhh I thought they got bought out. Nice to know they’re still around. I know they stopped the cards in … I want to say 2008. Used to love collecting them as a kid.

Glad you enjoyed the read 🙂

LikeLike